A Time Egg, Indeed: Why Chrono Trigger, and Video Games, are Art.

January 6, 2014 in General Topics

The late Roger Ebert famously opined that video games were not art. The intensity of his stance softened with time, but he nonetheless never swayed from it. I’ve a lot of appreciation for Ebert’s legacy; his astute analysis of film–and his deep respect for movies as cultural artifacts–but I was surprised when I learned of his disregard for this medium. It’s bothered me for some time. I recently replayed a video game I’ve always cherished, one I seem to revisit every few years, and it dawned on me: I’m ready to address this subject.

What follows isn’t a rebuke of Ebert specifically, but instead the notion that video games belong in a comparative doghouse next to other forms of entertainment. To buoy my points, I’m going to use what–in my opinion–is the greatest video game of all time. That game is Chrono Trigger.

A disclaimer, up front: After I wrote this, I realized pieces of it seemed egotistical. But this game matters to me on a very personal level, and I can’t talk about that connection without talking about myself. So please, bear with me.

Here we go: Video games are art, and Chrono Trigger is a classic example as to why.

On its surface, my key piece of evidence is hopelessly anachronistic. Chrono Trigger is miniscule compared to its latter-day counterparts. Its 60MB in size is nothing; you could fit over fifteen thousand copies on your average one terabyte hard drive. Its character sprites are simple; its interface primitive by contemporary standards. The music, magnificent though it may be, is rendered solely in 16-bit. The original box art doesn’t stand out (and I’ve actually never cared for it).

On its surface, my key piece of evidence is hopelessly anachronistic. Chrono Trigger is miniscule compared to its latter-day counterparts. Its 60MB in size is nothing; you could fit over fifteen thousand copies on your average one terabyte hard drive. Its character sprites are simple; its interface primitive by contemporary standards. The music, magnificent though it may be, is rendered solely in 16-bit. The original box art doesn’t stand out (and I’ve actually never cared for it).

Chrono Trigger carries no celebrity endorsements. This is no Citizen Kane, lavished with one deconstructive retrospective after another in highbrow magazines. It doesn’t appear on an institute’s list of sacred cows. You won’t find it in a gallery, looked over by those given to wine tasting.

It gets worse, too: the game is almost twenty years old, made for a long-discountinued console. It has no endless trail of increasingly-sophisticated sequels, like the legendary Final Fantasy series. Someone might take a look at a few screenshots and promptly disregard it.

So how do I make my claim, especially with this game? How do I hope to answer the Eberts of the world?

I think three attributes define art. It’s a bit like the fire triangle, but instead of combusting, these characteristics make the human spirit glow.

First, I’d argue that for something to be considered art, it has to elicit a strong emotional hold that lasts.

The middling is soon forgotten. That’s why contemporary bodice-rippers are largely doomed; why our bookstores aren’t stacked with a plethora of nickel westerns. Disposable fiction doesn’t last.

Chrono Trigger looks like a simple, blissfully old-school game on the surface, but what it lacks in technical complexity, it more than makes up for in storytelling. It starts formulaically enough, with its eponymous hero, Chrono, leaving his house for a day at the fair.

But make no mistake about it: this is a rabbit hole of a tale, one that can stand alongside the better science fiction stories of the last century. The creators of Chrono Trigger spun a multi-layered, complex progression of events, and every time you think the adventure’s scope has broadened to its apex, it expands outward even more. This game is a mindbender, full of interweaving plots, where minor decisions can impact the very course of the world.

But make no mistake about it: this is a rabbit hole of a tale, one that can stand alongside the better science fiction stories of the last century. The creators of Chrono Trigger spun a multi-layered, complex progression of events, and every time you think the adventure’s scope has broadened to its apex, it expands outward even more. This game is a mindbender, full of interweaving plots, where minor decisions can impact the very course of the world.

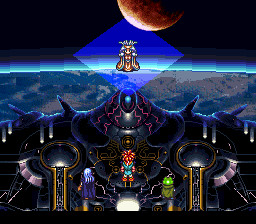

It’s one of the only games I can think of that gives you the ability to literally ignore its own mechanics. One can end the game very early on, for example, by taking on Lavos, the primary antagonist and final boss. Technically, this resolves the story, even if the resulting ending is dire:

And let’s talk about Lavos, for a moment. Though Chrono and his friends are given the chance to confront it at any time, you’re actually rewarded by hanging back and progressing through the various time periods exposed by the game’s many “gates” (and later, by the amazingly-slick time ship, Epoch). You learn more about your foe this way, and how it impacted and shaped the very world it assaulted.

You learn more about your foe this way, and how it impacted and shaped the very world it assaulted.

That Lavos will destroy the world if nothing is done is a given; the player watches it happen early on. The alien force makes no attempt at hiding its multiple attacks on mankind (and the game’s other inhabitants). It is the worst sort of villain: the unflinching, detached, unapologetically evil variety. It is a locust, a leech, a tapeworm; or–perhaps, to really hit it on the head–a parasitoid wasp. Its tendrils of influence impact multiple parties over the course of the game’s many time eras.

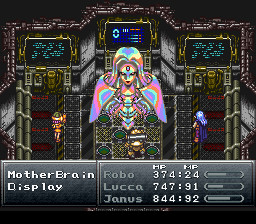

This divergent group of characters includes many friends and foes, and some that delightfully straddle the difference in-between. Among these is Magus, who is easily one of the most compelling and internally-conflicted characters in video game history. An entire book could be written (and should be written) about just Magus’ experiences alone, and you’d find legions of people lining up to buy it.

This divergent group of characters includes many friends and foes, and some that delightfully straddle the difference in-between. Among these is Magus, who is easily one of the most compelling and internally-conflicted characters in video game history. An entire book could be written (and should be written) about just Magus’ experiences alone, and you’d find legions of people lining up to buy it.

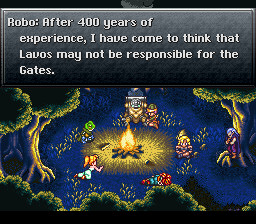

This is world-building that stays with you. I keep coming back to Chrono Trigger like a beloved movie, or a treasured album, and for myself and so many others, it thus satisfies that first aspect of art. It was one of many works that gave me a love for epic fiction. Its impact has been felt by many, in similar ways. So it satisfies that first criteria, and also the second:

Art ingrains itself into the consciousness of a group of people.

Let’s turn the Epoch’s dial to the future (or at least, what I hope is my own future).

Every writer is a dreamer, and so we spin about possibilities, like being interviewed on TV one day, or the like. We can’t help it. In my case, maybe my moment in the sun would happen if the Beacon Saga made it big, or some other work I wrote was made into a film. And the manicured interviewer is asking me about my influences, and one of those that I mention is Chrono Trigger. And there’s this moment–I can see it crystal clear–where they find out what it is, shake their head, and say “A video game?”.

But then I look around the room, and I see people from all sorts of backgrounds, and they’re all nodding their heads, because they remember Chrono Trigger, and it’s as laced around their bones as calcium. And they can’t explain why, at least not in most of the circles they’ve known. And that’s okay, because we understand each other in that moment, because we’ve been unified in the way that truly powerful fiction brings people together.

Third, there’s the test of longevity. How long, exactly, will Chrono Trigger–and video games in general–endure?

Let’s turn the time dial even further ahead.

I’m old, very old. Outside, the mist rises over the mountains, seen from the window of that cabin I always imagine having, and the light catches the glimmer of twinkling aerocars plying their lanes. The grandkids (or great-grandkids) are running around, out in the dewed lawn, with their ocular projectors on, playing some sort of immersive experiential construct.

My daughter and I watch from the large windows looking out from the upstairs office. We get into the topic of video games, and the days of the consoles, and the rise and decline of tablets. We start talking about the games we played together, including some of the ones I introduced her to when she was young. She remembers me imploring her to try Chrono Trigger, of course–it was already old when she first played it.

Everyone that worked on the game is long gone. We would have heard about how the last developer connected with it passed on in Hawaii six years earlier, or something similar. And while my daughter and I talk, I get nostalgic, and fire up the OLED wall–and there’s the Chrono Trigger logo waving its way across the screen, ten feet wide and two feet tall.

The game isn’t just “retro” anymore; now it’s an antique. The 16-bit characters look garish on the wall, and the tonal edge of each musical note is omniprescent over the cabin’s sound-emitting structure.

I can’t use my well-worn, authentic SNES controller, not since the arthritis–but my daughter can. And when she pushes “start”, it all comes back to us.

I can’t use my well-worn, authentic SNES controller, not since the arthritis–but my daughter can. And when she pushes “start”, it all comes back to us.

There’s the Millenial fair, ever-celebrating, and there’s Lucca. Waiting at the beginning of it all.

Back in our present time, there’s a thousand people out their reading this post, and they’re nodding their heads, and maybe you’re one of them. Because this game left its emotional mark.

And–here’s the key–it will continue to do so long into the future.

Some of the greatest artifacts of mankind are also some of our greatest masterpieces. Some cities have several within walking distance: the Arc de Triomphe, Eiffel Tower and Pont Neuf are just a few one can visit in a single afternoon in Paris.

But these artifacts are in some ways cursed by their own uniqueness. What makes them special can be their undoing–a simulacrum of them is not, generally, considered equivalent to the original item.

Were Epoch around, we could take it to witness many moments marking the loss of irreplacable art. We could see the Colossus of Rhodes topple over in an ancient earthquake. We could watch the Library at Alexandria go up in smoke, along with its many masterpieces contained therein. We could see irreplaceable churches being bombed in the world wars. We could witness an Eygptian sarcophagus get melted down and sold. We could linger as an oil-on-canvas painting goes up in smoke, or as new rulers dispense with the statues of the old, toppling them into the rubble of fallen dynasties.

Chrono Trigger and the electronic art of our society have, ironically, a uniqueness inherent in their continued propagation. They will be around, safely ensconsed within the ecosystem of the Internet, like mayflies forever breeding and dying. Every day, we lose hundreds of copies that are replaced by hundreds more.

At 60MB, Chrono Trigger’s chances of outliving us go up: even if the Internet vanished tomorrow, if civilization collapsed, our storage devices would last eons before they all disintegrated, and it wouldn’t even require near as many surviving sectors of a millenia-old drive to keep a copy of the game intact as it would one of the behemoth games of today, or their eventually-gargantuan ancestors. As available storage continues to increase, so too do the chances that some far-future visitor–maybe even our own descendants–would re-discover Crono’s swordplay, or Frog’s struggle for redemption, or perhaps the lofty and misguided people of Zeal. That it is “just a game” won’t matter–a lost culture’s games are often prized artifacts, treated as treasures.

Such a discovery might even happen at our equivalent of Chrono Trigger‘s 2300AD, in some far-off future where an accidental or deliberate archeologist might think we’ve left nothing but ruins, where civilization is perhaps consigned to androids and outlaws.

I say we’ll have left such a future discoverer something else. I say we’ll have left them Chrono Trigger. And they’ll call it art.

![]() A young couple in a childless, refugee space fleet at the last star left in the Universe gives birth to a miracle child. A specter from the past returns to confront mankind…and the end becomes the beginning. Try Part I of the Beacon Saga Serial, for your choice of ebook platforms.

A young couple in a childless, refugee space fleet at the last star left in the Universe gives birth to a miracle child. A specter from the past returns to confront mankind…and the end becomes the beginning. Try Part I of the Beacon Saga Serial, for your choice of ebook platforms.

Recent Discussion