Five Great Historical Battles, Part 3

August 9, 2012 in General Topics

We’ve finally come to the last post in this series. We’ve seen a wide variety of conflicts, spanning multiple theatres and time periods, from medieval Japanese shores to the frontiers of Colonial America. And we’re going out with a bang. I’m pleased to bring you not one, but two final conflicts that are worth covering.

That’s what I do, here, folks – always deliver a little more than you expect.

Once more into the breach!

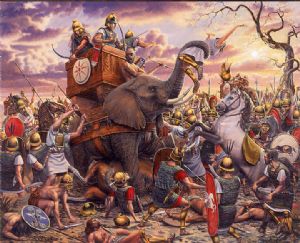

Battle of Zama, 202BC

This series has tried its best to focus on battles that were profound not just in size, scope, or combatants involved, but also were events where the course of history itself hung in the balance. We’ve often found ourselves turning the spotlight on legendary individuals. So what better battle could we include in this list than the Battle of Zama, which included two such men?

You’ve heard of the first combatant, the Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca. He’s at the gates, you know. Rome’s ultimate boogeyman came closer to conquering the Republic than perhaps any other single person. (Forget Attila the Hun. Attila was mainly interested it being an extortionist.)

You’ve heard of the first combatant, the Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca. He’s at the gates, you know. Rome’s ultimate boogeyman came closer to conquering the Republic than perhaps any other single person. (Forget Attila the Hun. Attila was mainly interested it being an extortionist.)

Hannibal was a voluntary change agent and wanted to settle for nothing less than the end of the Roman Republic. He was a genius at the fine art of making enemy forces fight the battle he wished them to fight. The story of the Second Punic War’s early years could be paraphrased as: “Hannibal raises more troops. Romans send huge counterattack. Hannibal manipulates circumstance. Hannibal scores crushing victory. Romans panic. Hannibal raises more troops.” Rinse, repeat, offer a sacrifice to Jupiter.

Facing Hannibal was a man you probably haven’t heard of: Scipio Africanus.

Facing Hannibal was a man you probably haven’t heard of: Scipio Africanus.

Scipio demonstrated a natural charisma from an early age, coupled with a disciplined intelligence. He was poised to become the ultimate foil to his macro-focused adversary.

Scipio and Hannibal finally met in 202BC, in North Africa, on the eve of what each man knew would be a clash for the ages. Oh, to be a witness to that conversation. We’re told there was mutual respect and admiration. You rarely get that kind of thing between two people embracing their role as change agents.

Negotiations – if they could have really been called that — broke down, and the Carthaginians and Romans prepared for a fight.

This was the battle that Scipio, a rising star, had been waiting for. He had an excellent force of light and heavy cavalry, and the always-solid Roman infantry.

Hannibal was determined to reverse the course of his people’s decline, and came prepared. He had a confederation of mercenaries, defectors, and 80 of the infamous war elephants. He also outnumbered Scipio by some 10,000 men, according to most sources.

Interestingly, it might have been the presence of the elephants which provided the most ammunition for Scipio’s use. He had his infantry formations prepared to open gaps in their lines, allowing the elephants to charge through and become dispatched elsewhere.

In an ingenious maneuver, he spooked and disorganized the pachyderms using loud horns, blown by men in his cavalry units. Some of the elephants panicked and scattered back through the Carthaginian left flank, throwing it into disarray, which Scipio’s number two man – the future King Masinissa – quickly exploited. The remaining elephants, charging the Roman line, were picked off according to plan.

Back in formation, the dirty work of an infantry slug-out began, with the three lines of each force taking substantial losses, particularly the skirmishers and light infantry in front of each army. Eventually the Roman cavalry, having run off their counterparts, returned and attacked the rear of Hannibal’s third line, turning the fight into a wholesale slaughter. Hannibal and a modest contingent of his men survived the defeat.

Scipio displayed surprising leniency to the Carthaginians, and allowed Hannibal to keep public office in Carthage. Unfortunately for Hannibal’s Latin and Roman allies, the less-rosy outcome was beheadings and crucifixions.

This was the last time the North African power would threaten Rome. Forced into a brutal peace treaty, their power was sapped for good. Some 70 years later they were again attacked by the Romans, and crushed. Carthage itself was raised to the ground.

It didn’t all end well for Scipio, either. Derided and disregarded by his people in the years to come, he went so far as to refuse burial on Roman soil. A tomb inscription attributed to him supposedly read: “Ungrateful Fatherland, you will not even have my bones.”

Roman dominance in the Western Hemisphere led to an unparalleled influence in future world events. Anyone with even a rote understanding of history could acknowledge that. It’s difficult to imagine a world without the eventual-Empire of Rome, but if Barca had pulled off an upset at Zama, it would have certainly been possible. What would history have looked like had it recorded a Pax Carthaginia instead?

The Battle of Delhi, September 28, 2032

Military history has a habit of rendering moot supposedly-impenetrable obstacles. Dramatic results can await the commander gambling his forces on an audacious maneuver through such terrain. Hannibal had the Alps. Washington had the Delaware River. Hitler had the Ardennes Forest.

Tak Akita had the Himalayas.

Akita was a man apart from his contemporaries, a half-Filipino, half-European juggernaut that openly derided international law, and cast global agencies as “neutered acronyms” that had done nothing while his people suffered under the Lord of Manilla in the early years of the 21st century. Akita led a successful revolt that freed his nation, but Philippine quarrels with mainland Asia — and Akita’s calls towards a Pacific Rim removed from “Pan-Chinese influence” — led to blockades, trade disputes, and eventually, war.

Akita took advantage of widespread social discord in China, casting himself as a liberator of downtrodden peoples. In a stunning upset, his navy knocked out the Chinese fleet, and invaded the country’s mainland, conquering it over two years of dogged fighting. General Akita had become the most powerful man in human history. This shocked the world.

It also brought other nations into an open alliance against him, including India.

Akita, now 39, had long-hinted at secret weapons programs designed “with special consideration to the needs of my preferred tactics”. Many considered his threat of such technologies so much bluffing, even after his successful deployment of the first combat holography on the streets of Beijing. The Allies believed great naval forces assembling in the Indian Ocean — together with the natural barrier provided by the Himalayas — would form a base of operations for troops and resources being leveraged for a counter-offensive.

But on the morning of September 27, 2032, independent Nepalaland began sending urgent pleas for international assistance from the allied nations. Incredulous commanders looked on as video streamed from the Himalayas showed the impossible: armored vehicles were zooming over the mountain peaks. One well-known photo from the period, leaked out of the invaded nation, even showed a hovertank cresting Everest.

The daring maneuver cost Akita large numbers of APC’s, tanks, and supporting aircraft. Gale-force winds sent whole companies colliding against cliff faces. Intercepting aircraft targeted the slopes themselves, burying alive units in avalanches and rock slides. Engines failed and left their vehicles plummeting into chasms, or their isolated occupants freezing to death.

Akita, however, could afford these loses. It rapidly became clear that Nepalaland, easily swept aside, was not his primary target. A panic set in along the Nepalese-Indian border. Soon his huge formations, their vehicles dotted with melting snow, streamed down into the 100-degree heat of India, and engaged in direct combat with the country’s unprotected northeastern flank.

The armored regiments moved fast, seizing vital factories, overrunning civilian cities, and wiping out pockets of resistance. By the night of September 28, Akita’s victory flags hung over the beleaguered citizens of Delhi, and his holo-propaganda adorned the city streets.

India capitulated, and reluctant officials turned themselves over to Akita’s prisons. Those that cooperated would be released, taking positions as local administrators, but those that proved recalcitrant would spend the rest of their lives working as slave laborers.

With the conquest of India, Akita had cemented himself as the most dangerous military leader of all time. Decades of global war, environmental destruction, and civilian misery would follow, culminating in the collapse of a number of nations, but the most lasting result of the Battle of Delhi was the need for the Nartuni/human treaty, which established the Serpican Police, and helped ensure Akita’s defeat. With better care and more heed to Akita’s posturing, the Allies might have turned him back in India. Had he been defeated at Delhi, the alien-equipped Serpicans might have never existed, including their enforced peace so reluctantly accepted by the leaders of Earth’s nations.

This concludes our series. I do hope you have enjoyed it. Make sure to check out Sojourns Through Troubled Worlds, my short fiction collection, for some killer science fiction adventures (and I recommend “Paston, Kentucky” for you military sci-fi nuts). For more on Tak Akita and the Earth of 2142 left in his wake, check out The Tyrant Strategy: Revenant Man, coming soon to a pillbox near you.

Stay tuned.

Recent Discussion